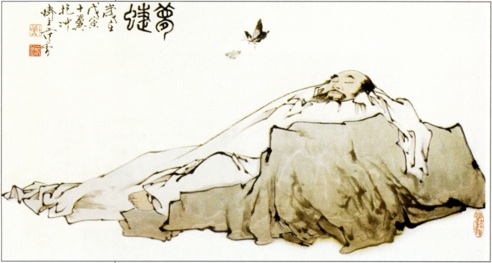

The Zhuangzi, Chapter 29.

Chapter 29, more specifically the passage focused on Robber Chi, might be interesting to read as the two main characters Confucius and Robber Chi challenge the reader's idea of the "good" character from the "bad" one. Confucius, while in dialogue with Chi, mentions three virtues. The first goes as such:" I have heard that in all the world there are three kinds of virtue. To grow up to be big and tall, with matchless good looks, so that everyone,young or old, eminent or humble, delights in you - this is the highest kind of virtue". The second virtues are wisdom and eloquent speaking while bravery and fierceness are mentioned as the third. These virtues mentioned by the mocked Confucius in a text written thousands of years ago are still very present in today's modern ideologies. Looks and appearances are very much valued and cherished by most western societies as most important in life. An example of this would be the "photo or no photo" debate, which argues the inclusion of photographs in CV's as many employers base their decisions on whether the candidate may be attractive or not, rather than focusing on their professional experience.

Another virtue mentioned in the text is the hunger for power. In some cases, people choose different means to attain their goals. Achieving goals may require a strong mentality and a powerful will, especially if the goals set are hard to achieve. However, that should not force someone to change their personality or behavior in a negative way to attain them. Liu-Hsia Chi, for example, had a brother named Dao Zhi who, with 9,000 followers, dug through walls and broke into houses (driving away people's cattle and horses, and carrying off people's wives and daughters) in order to enjoy a good reputation and have some sort of credibility and power. One of the morals that can be learned from this text is that no matter who you are or what position you have if you do not own these characteristics you will not benefit from a good reputation.

Another point in question throughout the text is the definition of happiness, which has been one of human's main concern and a topic of discussion (such as philosophy of happiness analyzed by the likes of Aristotle, Socrates, and Kant, for example). As individuals, people might spend their lives setting objectives thinking that they might reach a certain level of happiness. However, for some, once happiness it attained, they realize they might want more. To what extent may one fix these objectives? And is it possible to define happiness?

Throughout the text, some may understand that no one has the right definition and everyone should listen to his or her inner voice and follow one's own path. What makes happiness unreachable are regrets, as psychologist Marc Muchnick points out in an article on the online magazine Psychology Today. By silencing the inner voice inside each individual and listening to others, regrets are likely to be formed. One day he or she might wake up and realize how much time may have been wasted living the life that others wanted them to live. This innate desire to strive for success is highlighted and, most importantly, criticized in this chapter.

. (2016). Forbes. Retrieved 15 May, 2016, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/robasghar/2013/07/22/no-photo-on-your-resume-and-other-career-advice-you-should-question/

. (2016). Psychology Today. Retrieved 15 May, 2016, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/no-more-regrets/201101/the-regret-factor-how-it-impacts-our-happiness

No comments:

Post a Comment